Introducing TP: A Zero Trust Secure Proxy

November 15, 2023

Over the past few years I’ve been building a significant infrastructure that contains a network with great connectivity, state-of-the-art compute capabilities based on Kubernetes, and a lot of automation to keep it running.

This serves as a great testbed to experiment with and implement all sorts of technologies, including a Zero Trust security model. That’s increasingly more popular today, with many commercial offerings to help enterprises reap its benefits.

As you can see in my previous posts, I have built an ACME CA which I am using to issue TLS and SSH client certificates to all of my devices, such as my laptop. That’s great, but how can I connect to all my services now using these?

I wanted to start with a goal: I can use my laptop in most networks out there, perform any action, such as connecting to internal services, trying things locally, etc. and don’t require a VPN. Although I have one, I want to not have to use it, for as many things as I can get away with. Moreover, taking it one step further, one day be able to remove all special IP addresses from access lists, firewall rules, configuration files, etc.

Every time I need to connect to a service, I should be able to prove my identity and my authorization to do that, no matter where I am. And if possible, passive data collectors on the wire should be none the wiser on what I’m doing.

This is why I built “TP” a few years ago. Although it’s nothing new, I spent the last couple of weeks modifying it significantly and adding some new functionality that I think is blog post worthy :)

What is TP?

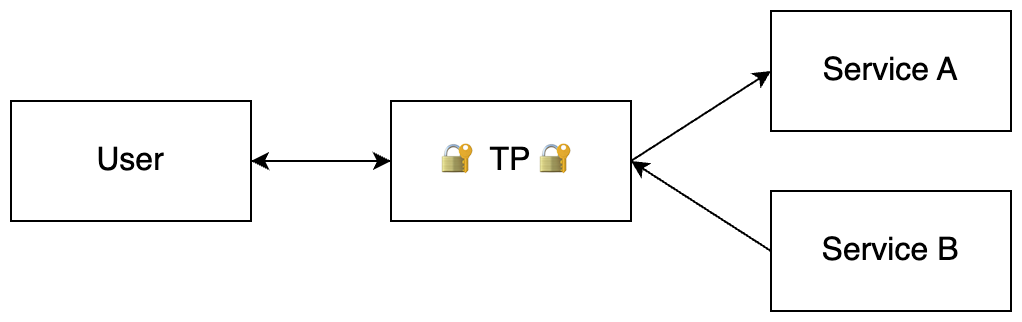

TP is a piece of software that listens for connections on TCP port 443, requiring a TLS client certificate to proceed, and then giving the dialer a couple of proxying capabilities:

You can request TP to open a TCP or UDP connection to a destination, and then

pass it over to you for direct access. This allows you to connect to e.g.

mail.daknob.net:993 and everyone on the network will see a normal “HTTPS”

session with a web server on the Internet.

You can request it to open a reverse connection. This is similar to services like ngrok, where you can expose a local port to the Internet at large, from anywhere, without any port forwarding, or firewalls, by proxying all the traffic through TP.

The name comes from the words “TLS Proxy”, but it’s more than that: it will authenticate all requests being made, and it will ensure the appropriate credentials are authorized to perform such an action. It essentially acts as an Identity Aware Proxy but for non-HTTP traffic.

This is very useful for cases where a service is really difficult to expose on its own, or would require significant modification or limitations before feeling comfortable to do that. In an ideal world, this wouldn’t be needed, but until we get there, it has to do. What’s an example of such service?

SSH

The first use case that TP was created to serve was SSH. I need to be able to remotely administer all of my devices securely. Although the SSH certificates from my previous post go a long way, there are still a few problems:

- Roaming devices do not always have a public IP address without any firewalls

- Requiring access from anywhere means all SSH daemons need to be exposed to the open Internet

- There are public WiFi hotspots or hotel networks out there blocking

22/tcp - The TOFU nature of SSH is not ideal

By ssh’ing over TP I can establish a TLS connection on 443/tcp to the closest

proxy and then it will take care of patching me through to the server’s SSH

port, within my own network or cluster, using any transport protocol I want,

transparently.

Convenience

Does that mean that every time I need to SSH into a server I have to do something like this:

tp-up example.org:22 1234

and then connect to localhost:1234? No! That would be very bad UX.

Instead, I am taking advantage of SSH’s built in ProxyCommand. Every time you

connect somewhere, if you specify this parameter in your command, the ssh

binary will run the value of this as a shell command, and instead of making a

network connection to the target, it will instead pass all outgoing traffic to

this shell command’s stdin, and process incoming traffic from this command’s

stdout, all while printing its stderr to the terminal.

An example here with netcat would look like this:

ssh -o ProxyCommand="nc %h %p" user@example.org

Now instead of connecting directly to example.org, ssh will spawn a nc

process with the arguments example.org and 22, and then use that to

continue the session. Since netcat simply starts a TCP connection, this won’t

do much, but with TP’s client this will send all SSH traffic over the TLS

tunnel.

The nice thing here is that this doesn’t have to be SSH aware! We’re simply

io.Copying bytes from one place to the other at the proxy, and everything is

kept end to end: your list of trusted hosts is on each device, you don’t need

SSH agent forwarding, or anything like that!

Since I work a lot with network devices, such as routers and switches, I

maintain ossh as a terminal command that bypasses this, so I can use this for

e.g. direct local connections over a management interface.

But what about roaming devices?

Reverse shell connections

Since TP can start a connection from any laptop, we can instruct our device to

maintain a connection with the proxy forever, and then just expose 22/tcp to

it. Now everyone can dial in from anywhere!

But isn’t that bad? Yes, probably. This is why TP has two modes of exposing services in a reverse connection: you can either make something available on the Internet, such as a game server, or it can expose a service through the same rigorous End to End Encryption requirements of the rest of my infrastructure.

It’s therefore able to perform all the authentication & authorization both ways. It will get a new TLS Server Certificate for the SSH port of each laptop or desktop, automatically via ACME, and keep renewing it. It will then demand to see a TLS Client Certificate for every connection, it will check against its list of naughty and nice, and it will only forward it for authorized devices.

Every time I need to connect to a laptop’s SSH port, I can now just talk to TP, prove to it I’m able to use it, ask it to patch me through to the end device, and prove to it one more time I’m cleared to do that. And that’s it!

How does it work?

Let’s talk a little bit about how TP works at the application layer to efficiently route connections through. I won’t go into my authentication & authorization for my Zero Trust setup, as this deserves a post of its own.

Outgoing Connections

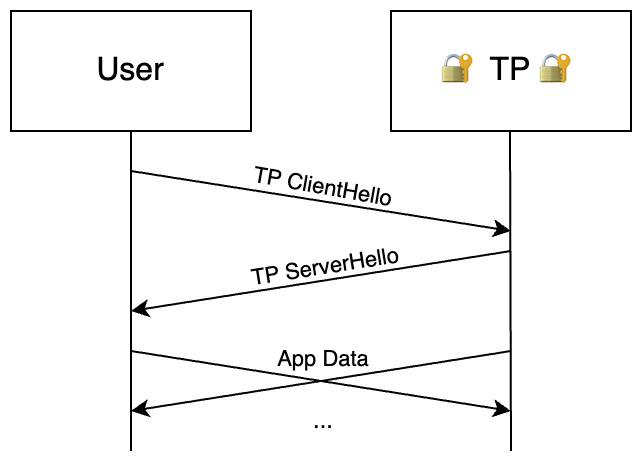

If you want to connect to some internal or external service, you establish a

TLS connection to the proxy on 443/tcp with your 4 hour Client Certificate.

If you don’t present a valid one, the connection gets dropped immediately,

before ever making it to the application layer. Although this is on port

443, this is a raw TLS connection, and not an HTTP one. And since I control

both ends, a minimum of TLSv1.3 is enforced on both servers and clients.

You then send a ClientHello. This has the same name as in TLS, but it’s a

proxy protocol struct, and they’re completely unrelated. It’s a simple

JSON string with a predefined set of fields: you tell TP where you want to go.

I have experimented with Protocol Buffers, which would probably be better, but

I ended up with JSON for better compatibility.

The proxy will then receive and decode the request, sanity check it, and if it

looks good, it will establish the connection with the target. In any case, a

ServerHello will be sent back to the client, informing them of the status:

what went wrong, or the fact that it’s ready to pass data.

After these two headers, the two sides will io.Copy (bridge) the two inputs

and the two outputs together, while keeping an eye out for problems.

It’s a very simple protocol on the wire and it does not cover every potential problem. If, for example an error happens on the connection of the proxy to the target, there’s no way to inform the client, or retry. You simply drop the connection and let the application handle it. It also doesn’t somehow adapt to significant differences in TCP connection quality between the two ends, other than basic things such as shallower buffers, that should hopefully leave the task to the OS and Go.

Reverse Connections

This part is more tricky as we have an additional problem to solve: when you listen on a port, multiple connections can be established to you. So how do we deal with that?

I explored the idea of creating some sort of multiplexing system and pass “TP

frames” on top of the TLS connection. That way you can have the proxy inform

the client of a new connection by sending a new frame that’s somehow different

from the others, e.g. by having a ConnectionID field on it.

All of that was too complicated to implement, and also had disadvantages, such as using a single TCP connection that could get its window reduced, so one bad apple could spoil the bunch.

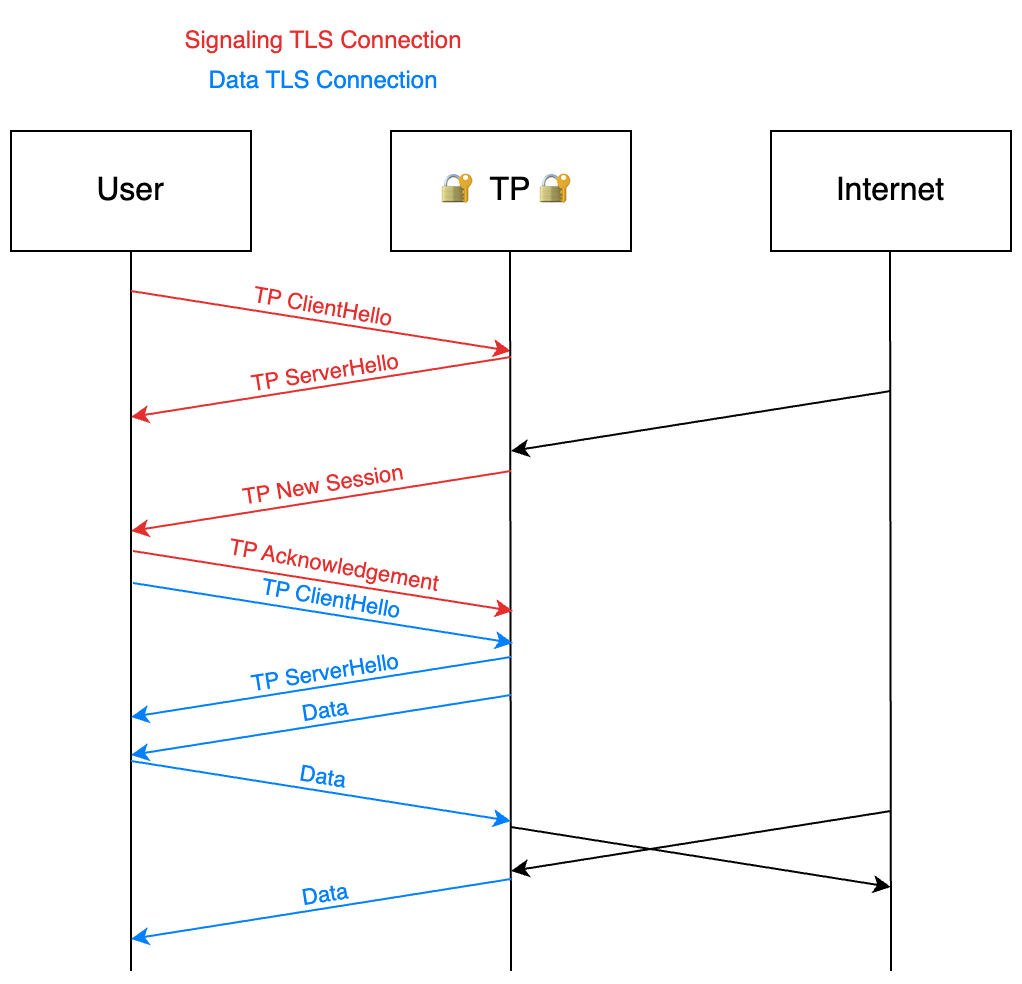

I decided to do this with multiple TLS connections: you start a main one, for

signaling, and send the ClientHello. The server responds with its

ServerHello, and this connection is now kept open. Every time there’s a new

session, the server informs the client, gives it a session ID, and the client

starts an additional connection, sends that ID in the ClientHello, and then

receives this over on the other socket.

This still has several disadvantages, such as making the signature of TP on the wire easy to classify, but for me, personally, strikes the right balance, as I have a small number of incoming connections that are low bandwidth.

Operations

From the above you can see that TP, especially for incoming traffic, is highly stateful. If you establish a connection on one process, you need to be able to keep talking to this process for the entire lifetime of this connection.

This means that if we want to do nice things, like running multiple copies, it has to be done in a smart and considerate way. All the traffic has to land to the same instance, all the time. If we have a single outgoing connection, we can expect that even with anycast and ECMP, this will “mostly™” happen.

But if we’re doing a reverse proxy, that’s not always the case: because the listener runs on the same instance that you established the signaling TLS connection on, all subsequent connections have to be established with this instance. Otherwise the other TP instance won’t recognize this session ID. And since they’ll have different source ports, if a 5-tuple is used for hashing on the network, it’s practically guaranteed to happen.

How can we get around that?

I have a few ideas, some good, some horrible, but I just played the “too small” card here, and I’m running one TP instance per data center region, and so far I haven’t run into any issues :)

What does it look like?

Well, there’s no UI, but my flow for the first SSH connection of the day is something like this:

$ dlogin

2023/11/16 15:56:44 Solving Challenge ID GgWQhhaqu_Bt

2023/11/16 15:56:48 Login successful!

2023/11/16 15:56:48 Expiration: 2023-11-16 18:56:47 +0000 UTC

2023/11/16 15:56:48 In: 3h59m58.198469s

$ ssh example.org

2023/11/16 15:56:57 Connecting to example.org:22 via tp.daknob.net:443 (v0.3)

[Normal SSH Session Here]

As mentioned in my other post, dlogin

only has to run once every 4 hours to obtain the necessary client certificates

using ACME, and then all other connections work normally.

The next generation

This piece of software has served me well for some time now, but there’s always room for improvements. And the past couple of weeks it received some big ones!

Let’s start with the thing that made all of that possible:

QUIC

Yes, the Internet is moving to QUIC and

it’s one big step to help TCP retire rest. It’s a new protocol that’s based

on UDP and comes with TLSv1.3 built-in! Its UDP nature allows for things like

packet ordering, congestion control, and many other aspects of TCP that have

ossified over the last

few decades to happen at the application layer and not on the operating

system, or even (worse) the hardware.

The next version of HTTP, called HTTP/3, works over QUIC, and tech companies like Google and Meta are now using it for likely most of their bits / second going out to eyeball networks.

How does QUIC work, and how is it integrated in TP?

With TLS we simply created a plain old TCP connection, and then ran TLS on top of it. But traditional TLS doesn’t play well over UDP. We need some of those guarantees to offer the service.

QUIC has the following two (simplified) data transport methods:

Stream

A stream is a unidirectional or bidirectional stream of data, in which QUIC guarantees the order of the packets, as well as their delivery. It’s basically similar guarantees with TCP.

Datagrams

Datagrams are the UDP equivalent: packets may or may not arrive, in any order, but unlike UDP they are encrypted end-to-end in transit.

In practice

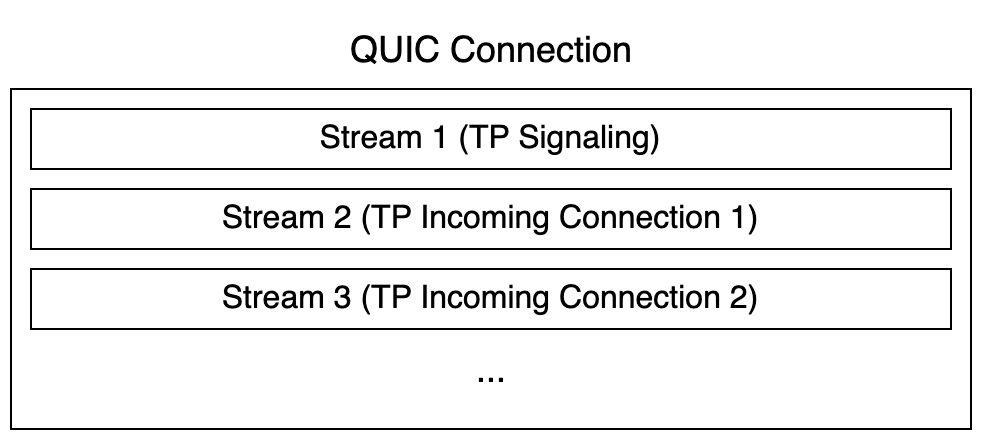

In practice, each QUIC connection can have zero or more streams, and one datagram channel. You use a single UDP socket and on top of it you can pass multiple connections in the same TLS context. Since it’s UDP, there’s no window size, no slowdowns, and you can multiplex ordered and reliable streams together! It’s also possible (but rarely implemented currently in libraries) to set relative priorities between streams. You also get a single low latency channel for unreliable connections.

What does this mean for TP?

We can now solve our incoming connection issue: we start one stream for signaling, and then provision and deprovision additional streams when needed. Each one of those is independent from the others by reliability, performance, and security standards. In a future iteration, a separate signaling channel can also be added for outgoing connections, too.

And since all of them appear as the same flow, it’s highly unlikely for them to end up in different TP instances under an ECMP scenario!

Wow, that’s a lot of problems taken care of with a single change. QUIC removes a lot of the software and operational complexity from TP… But it doesn’t end here?

QUIC will also send keepalives to ensure that the connection is still

available, and since it’s UDP-based, will do roaming! I can now switch my

laptop from WiFi to 5G to another WiFi and all of my SSH connections will

continue to work, transparently to the ssh command. How cool is that?

How can this ever be topped?

Well…

A problem that TP has is that it can’t work well on mobile devices. Doing all of that on an iPhone isn’t easy, or it maybe not even possible.

Enter WebTransport: it is a W3C Standard for browsers that allows JavaScript to get access to the creation of QUIC connections!

For several reasons it’s a little bit more locked down, but this is a very

promising primitive to one day create TP.js. You could SSH from a browser

directly to a device, or you could implement any other TCP or UDP protocol,

like MySQL, SMTP, or IMAP.

Currently only a subset of that is working, and it takes Chrome on a desktop for the full functionality, but maybe one day it can come to Safari as well. There are a few interesting things being done with WebTransport that will make this a very useful library to have, such as very low latency video and audio streaming. Let’s hope it’s enough to accelerate adoption.

Are we done?

Not yet!

Since QUIC is, you guessed it, UDP based, you can establish Peer-to-Peer connectivity in a much more reliable way. Using ICE you can create direct QUIC connections between services without the need for a traffic relay. I haven’t explored the full realm of possibilities here, but an idea for a future version would be for TP to act as a match-making server between two TP-aware clients, and then allowing them to talk directly to each other. No need to occupy TP with proxying traffic when the parties can bypass it. This will require some thinking on where authentication & authorization happens, but it could be designed. If you want to learn more about P2P on the modern Internet, there’s an amazing blog post by tailscale on the topic.

Do we even need TCP?

Unfortunately yes. I am still running into places that are blocking 443/udp

so being able to fall back to TCP is still needed. And that’s a good reason why

I am a bit more reserved using all of QUIC’s unlocked potential, as it won’t be

available when the client falls back. It would take significant design and

coding efforts to ensure feature parity between the two with the limitations of

TCP which I don’t think is worth it, at least for me, and at least today. I’d

stick with good-to-haves for now that can be exclusives to the new stack.

But it’s the other way around too:

The whole backup plan for when TP (QUIC) fails is important for me, as I don’t

want to lose connectivity. In theory, a VPN can fail as well, but I wanted to

improve my resistance against firewalls. This is why TP can run on my web

servers: if enabled, a TLS connection to www.example.org can be demuxed past

the SNI stage and be

handled either by the HTTP stack, or by TP. This allows me to connect to e.g.

blog.daknob.net, and if I “speak TP”, I get access to the proxy, and if I

“speak HTTP”, I get the nice posts that are available. It’s non-HTTP Domain

Fronting! With the current

state of the libraries, doing this in TLS is a few lines of Go, while doing it

with QUIC is quite a bit more complicated. Especially with

ALPN

into the mix.

Summary

TP has been really helpful in achieving my goals towards Zero Trust. Almost all of my SSH sessions go through it, and a few other services are made available on top of it as well. It provides a secure way to get in my clusters from anywhere, double checking that all connections are authorized, and providing an additional layer of encryption and obfuscation on top.

The “product” aspect is however more challenging: I don’t want to end up

building a per-port ACL’d VPN (Wireguard + nftables can do it well enough),

or another tailscale, so the places that require the

usage of TP in the happy path should be fewer. That is however a problem with

Zero Trust in general. You can just replace your VPN and call it a day, still

trusting everything within your own network. I am always looking for more ways

to create a “better” environment, however one defines that. Being so generic

and protocol agnostic, my little proxy may be a dangerous impediment to

progress on this topic – even if it’s psychological and not technical.