e-Voting: Math vs. Implementation

July 9, 2015

Technology has a deep impact in most people’s lives today. We all use the Internet when possible and we seem to do almost all we can online. We pay bills, we buy food and goods, etc.

One of the things we don’t do yet is vote electronically for critical elections, like Government / Presidential Elections or a Referendum.

In the traditional voting process, millions of euros are invested in a single voting event because we think more people can walk up to a certain place and vote than can vote using an Internet-connected computer. We also don’t completely understand the technologies behind e-voting and we don’t trust them. This can be the case because we still have a fear for technology.

Researchers have been trying for years to come up with a voting system good enough to be considered secure and impossible to tamper. By involving encryption, signing, and a lot of mathematics, they created what’s considered one of the best models, Helios.

Helios, originally shown in an Academic Paper uses asymmetric cryptography to ensure and mathematically prove that nobody can tamper with the system at all.

So there you have it. Just convince your country to run the next election using Helios, and everything should be fine. Correct? Definitely not.

One of the most important things with Computer(s Science) is to understand that the theory / model and the practice / implementation have enormous differences. This also applies here. Let’s just assume that we have this model implemented. If a malicious party wants to tamper the voting or even cause it not to happen, they can do it.

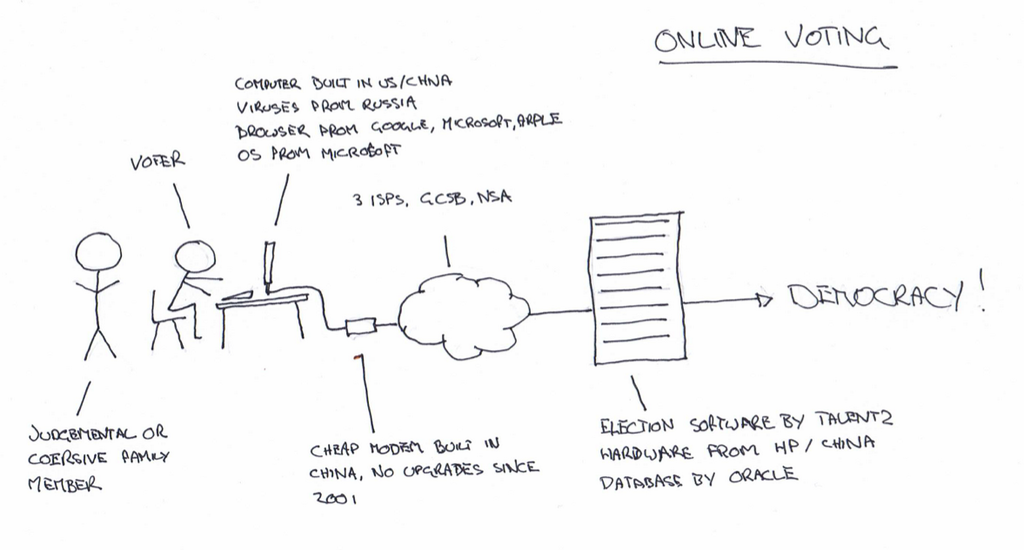

There are many points where the security of the system can be compromised, including, but definitely not limited to:

- The server hardware

- The voter computer hardware

- The voter network equipment

- The server network equipment

- The network equipment in the middle

- The server OS

- The voter OS

- The voter browser

- The voting software

Even if the code is perfect and has no bugs, something known to be impossible, especially at this scale, an attacker can hack into the server and replace the code running with her own version, that looks identical but actually isn’t.

This might seem not easy, and in some cases it’s not. I assume that if a country is running e-voting elections and people vote from their home, there will be an entire team behind this constantly monitoring it.

But what if the malicious adversary is a foreign government? What if they have spent billions and months of preparation looking for vulnerabilities to exploit and tamper with the results? You can never know.

Let me now tell you a story, a few months old. I was on Twitter, and saw a blog post that claimed we should try to have some elections, not the national ones, using a fork of Helios, Zeus. This fork is based on the same model, but has some small differences that allow for more types of voting.

The team that develops the software, a company funded by the Greek Government, called “GRNET”, also had a hosted version, available to anyone.

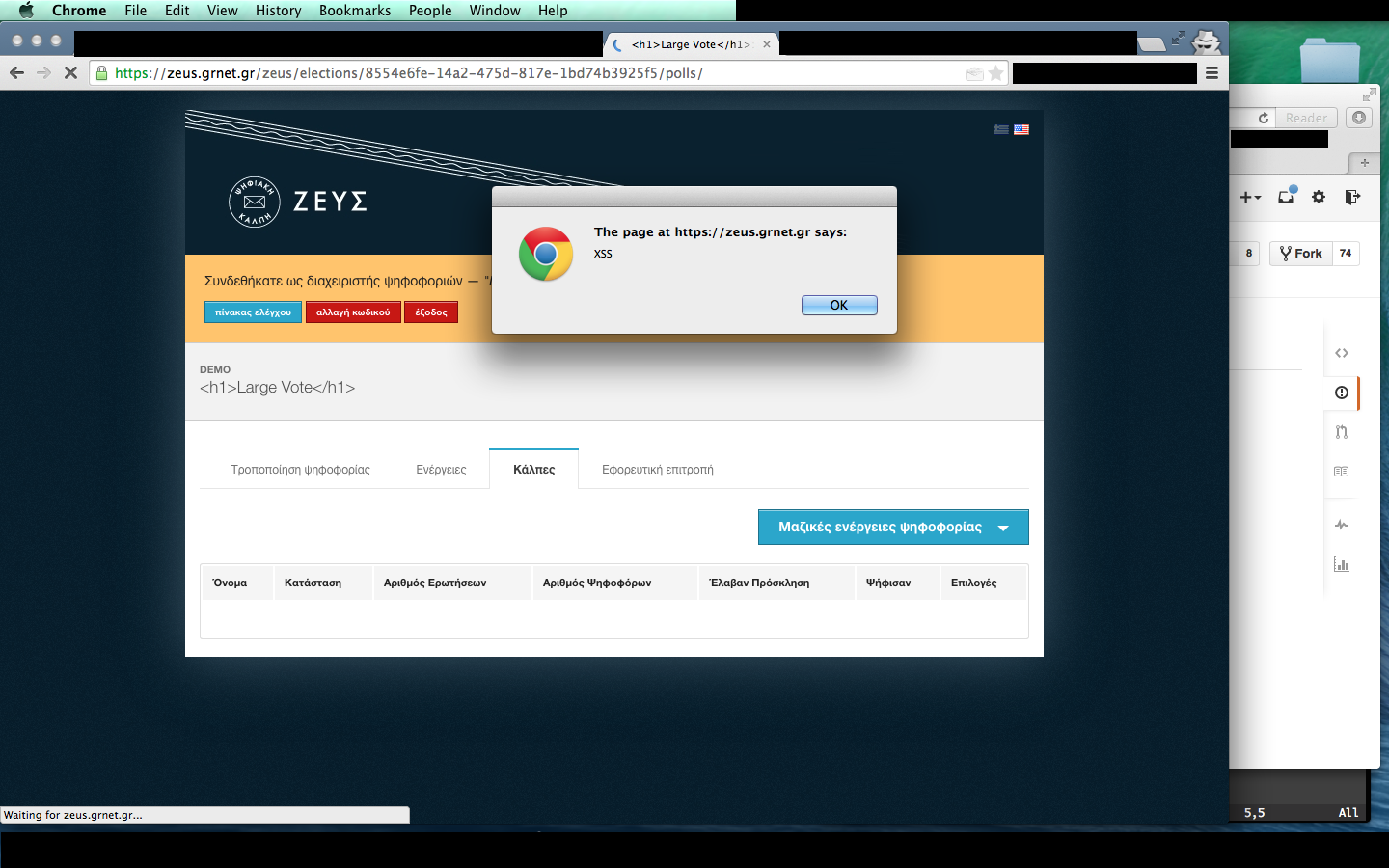

At this point I had about 30 minutes to kill, so I quickly created a demo account and started messing with it. Soon enough, on my first try, I discovered an XSS vulnerability, that affected the administrators of the platform:

This was a simple <script>alert("XSS");</script>. Nothing difficult. This could run arbitrary JavaScript in an Administrator computer as the Zeus system. With the appropriate code, one could perform actions as an Administrator without access to the account itself.

I reported the bug in their GitHub Repository and continued looking for some more bugs, in the remaining time left.

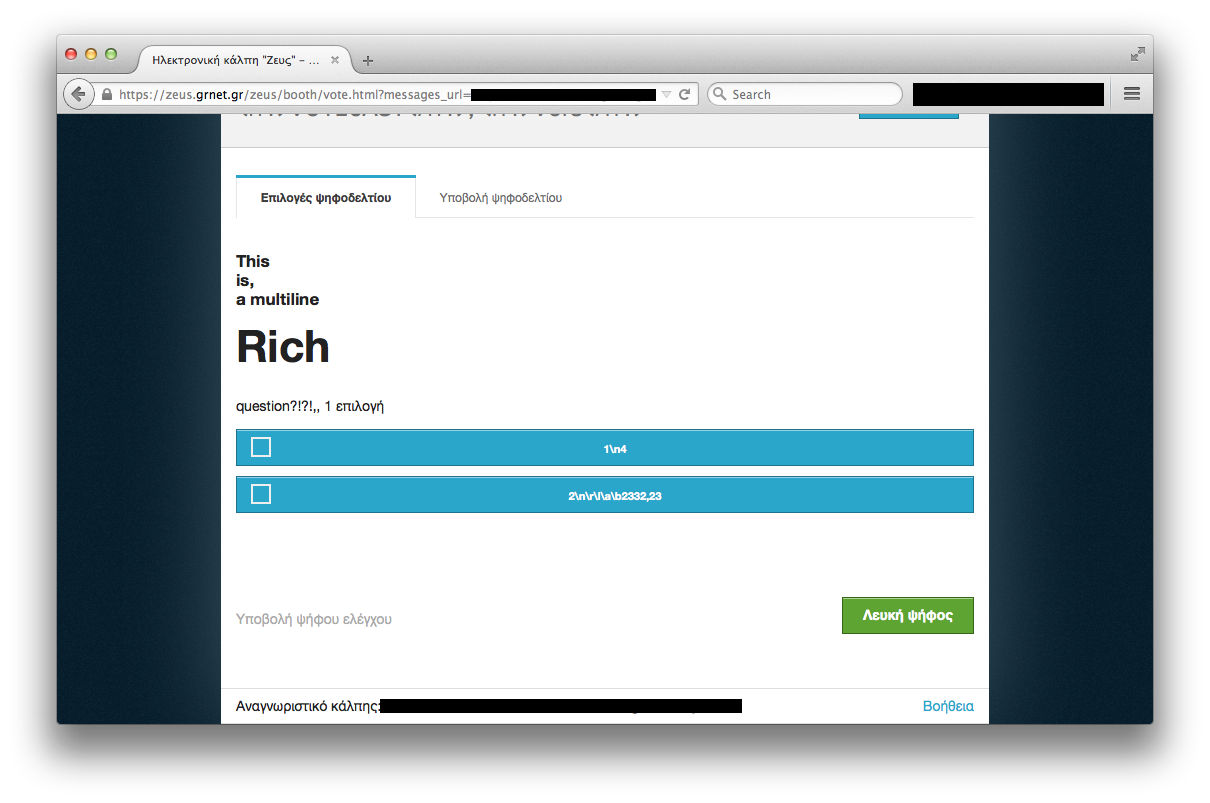

This time, something more important came up. The same payload as before, the most simple XSS attack that can be performed, but this time in a way more important part:

This is the screen where the voters select their choice. Ignore the “fuzzing” strings, and focus on the question title. Running JavaScript was possible but this time I went for a style manipulation, including an <h1> tag.

At this point, a malicious administrator could include appropriate code to arbitrarily change each voters’ choice without any detection from the server side.

The developers claimed that this would be detected in after the voting is completed, but then it may be too late.

I didn’t work on it any more time but these two findings were enough in my opinion to prove a point. If I managed to find two security bugs in less than 30 minutes on my free time, a government with hundreds of engineers and millions of euros could easily find more bugs that are more critical in the application alone, not including stuff like the web server, other services, etc.

Helios is a good model to work with. It even has functionality for external auditors to get the vote results and independently verify them one-by-one, even by your model-compliant software. But we currently lack an implementation for it that is secure. And, truth be told, I don’t think it’s easy to have one.

E-Voting for important elections can save millions, but currently we don’t seem to be able to perform one, since the things that could go wrong are simply too many and overcome any advantages.

At this point, your fellow management guy can come in and do some risk assessment. They may say that saving a few thousand euros on a local company voting is worth the risk of using e-voting. This is acceptable. But can a government take that risk? I don’t think it can do that yet. Maybe we can arrive at a point where this is an acceptable risk to take, but not today.

Finally, let me close with a nice picture that mostly sums ups what I said:

Regarding Zeus: The guys behind Zeus are a small team working without any funding trying to make this software better. They can’t afford an audit or more developers, so if you have some free time and want to do an audit or help in the development, please do so on GitHub.